In search of the lost feasts of childhood

Anne Thomas tries to eat her way to the past

“For her, as for me, the past had a sweet taste.”

I made faux gras. Never again! Why bother is what I first thought when I saw the recipe. I’ve never been a fan of ersatz (perhaps under the influence of my maternal grandmother who lived through the Nazi occupation of France). Since I stopped eating meat, I’ve preferred to go without sausage rather than suffer a bland tofu alternative. I’ve never found a meal made with substitute meat that tasted better than vegetables or pulses.

So why make a vegetarian version of a pâté that is the epitome of cruelty? The simple answer is glamour! Foie gras, like smoked salmon and oysters, recall the abundant Christmas and New Year feasts of my childhood. When I was little, we would cross the Channel by ferry (I already knew as a toddler how important the Dover-Calais crossing was) and the gustatory pleasures would begin on the train journey to Paris. There would be a crunchy baguette filled with ripe Camembert, a whole tube of Toblerone and a bottle of Orangina. This was France. Or was it heaven?

The next highlight of the holiday was the massive pre-Christmas shop at Carrefour with my grandparents. We would fill up the trolley with enough goodies to feed an extended family for weeks, and my grandfather, who had an unrivalled sweet tooth and had also known more frugal times, would pile it even higher with glittery boxes of chocolates and marrons glacés. On Christmas Day, relatives would arrive laden with fresh bread, platters of oysters, a Brie or two and inevitably a bûche de Noël. Lunch would always begin at 1 p.m. sharp, with smoked salmon and foie gras (there was half an avocado – more about this later – for the one vegetarian, my father, not a Frenchman bien sûr) and would continue into the early evening hours. This meal was not only about the food and wine, but also for catching up and reminiscing, re-telling the family legends, discussing films or books or arguing about politics.

But back to the foie gras. Even as a child, I was averse to it. I would like to think I understood that it was the product of brutality, but maybe it simply didn’t appeal. Like the oysters, I refused to even taste it. But one day, already a young adult, I took a bite of a canapé and had a revelation. This was no ordinary pâté; it had an intensity of flavour and a smoothness of texture that distinguished it and it was simply delicious. I was seduced. Had it not been for the cruelty of its manufacture and the fact that I would soon stop eating meat altogether, I might have been hooked. But I would also have been a different person.

However, what I have sometimes missed since becoming vegetarian is the sense of glamour associated with certain foods and the pleasure of eating something very rare on a special occasion. And this is what prompted me to try the faux gras recipe. I wanted to make something that would at least nod to those feasts of lore. I thought that in this craziest of years where travel has become complicated and large gatherings have all been banned, this pâté - which the writer assured would be indistinguishable from the real thing - was just what was needed at least to attempt to recapture the spirit of those banquets. Alas, I should have known that lentils and mushrooms did not have the same magic properties as a madeleine.

As 2020 draws to a close, it’s not only childhood that is a long way off, there is a sense that nothing will ever be “normal” again. Though the world had begun to cotton on to the severity of the climate crisis, the coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated the presentiment of doom. Trump’s defeat and the arrival of multiple vaccines brought a moment of respite in November after months in which it seemed as if we were hurtling towards disaster, but the new variant of the virus has put a damper on the excitement.

2021 looks set to begin as 2020 ends and nowhere does this seem truer than in Brexitland where I am currently stuck. There are hundreds of people dying daily and hospitals are full to capacity. All year, the government has struggled to communicate measures to prevent the spread of the virus in time; they have prevaricated, come up with new proposals and changed their minds. This rendition of Do They Know Its Christmastime? puts it very succinctly.

The Tories’ lack of consistency, their failure to plan ahead led last week to the abrupt closure of borders and thousands of lorries backed up on either side of the Channel. As Brexit negotiations were ongoing, supermarkets started announcing that there could be a shortage of lettuce, cauliflower and lemons. Then Lufthansa was brought in to airlift food to Britain. So that’s what they meant by taking back control!

Like Trump, the Tories are almost beyond satire. Just a few weeks ago, they were embroiled in a very “English” debate about what a “substantial meal” consisted of. All you need is a Scotch egg apparently and a pub can stay open (if you don't know what a Scotch egg is, you're not missing much, and you're obviously not British!). While such debates can still raise a laugh, the much more controversial discussion about whether to continue providing free school meals and rising food poverty in Britain is scandalous.

None of these subjects would be out of place in Pen Vogler's extremely entertaining and empathetic Scoff: A History of Food and Class in Britain. Reading the introduction, I chuckled at the following line: “A friend’s mother once said that, when she was growing up, you were middle class if your father had heard of Saul Bellow and your mother knew what avocado was.” Well - in case there was any doubt - I am definitely middle-class. As the child of non-British parents, never was this made clearer to me by others than through food. I learnt about British food traditions at school and at friends’ homes. Where else would I have discovered the pleasures of Marmite, Branston Pickle or treacle pudding?

It was actually a comment from a fellow Brit in Berlin that inspired this piece. We were discussing experiences of eating out as a child and it was suggested that I spent my childhood popping in and out of restaurants. In fact, I didn’t, but this is perhaps why eating out remains so special to me.

As the hospitality industry ground to a halt in early spring, I thought about which restaurant experiences I would like to repeat. I asked people I knew to do the same, as well as to tell me about their childhood experiences of eating out and what they were currently craving. For me, eating out as a child meant gorging on fast food. A special occasion for my brother and me was when our vegetarian father wasn’t home, and we would get fish and chips or - very rarely - KFC. My brother said that it was the deep-fried apple pies and milkshakes that had made most of an impression. I guess these had the most addictive additives. Friends too remember going to fast food joints. For one, Wimpy was the “height of sophistication”.

A takeaway pizza on birthdays was sheer joy, a tradition inherited from the American side of the family. My father and his brother remember pizza at Musicaro’s, a popular Italian place in Long Island, to which we made a nostalgic trip when I was a child. Another uncle of mine now makes the best pizza in New York.

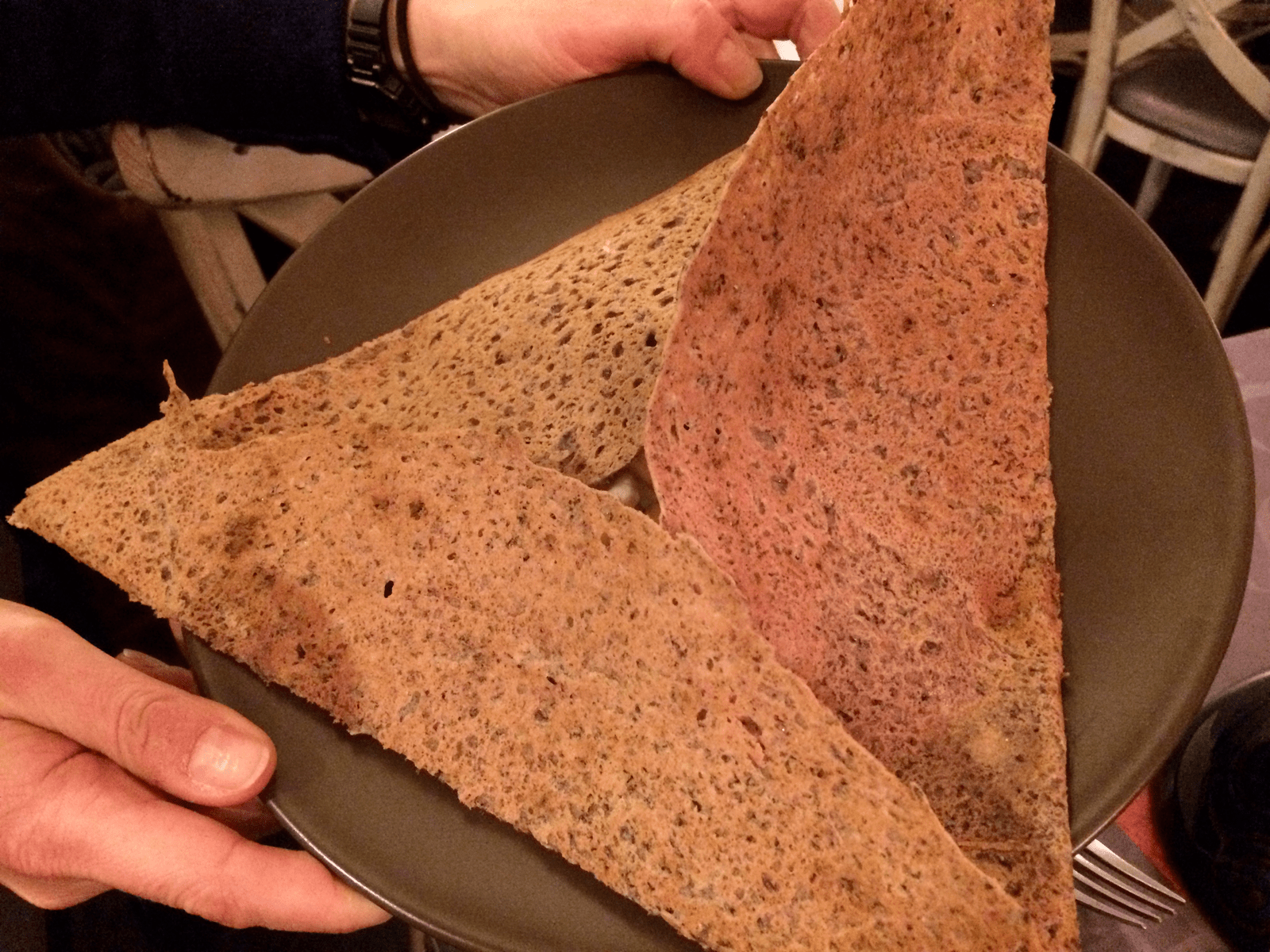

Thanks largely to the generosity of my grandparents, aunts and uncles, I also have some memorable experiences of “real” restaurants, which opened up new worlds to me. Over the years, my palate became more refined and though I would still die for pizza, it’s been a while since I stepped foot in a KFC! Before lockdown, I was lucky to have one of the most extravagant eating weekends of my life, not knowing that it was possibly the last of its kind. So I have no doubts as to which restaurant I would like to return as soon as I have a chance: Lode & Stijn in Kreuzberg for sure. Their March menu began with homemade sourdough, which I believe is some of the best bread I have ever eaten, and continued to enchant with ceviche of red mullet, pistachio and kumquat, followed by a dish of celeriac, Jerusalem artichoke and walnut. Desert was a pavlova with blood oranges and olive oil. All of this accompanied by a Silvaner that transported us to another plane. I dream of this meal.

I also hanker after noodles from The Tree in Berlin Mitte. Many of those who responded to my “questionnaire” apparently craved similarly spicy foods, from tandoori chicken and naan to that British classic “hot chips and curry sauce”. My yearnings for “exotic” food that I am not well-versed in cooking have been reminiscent of those nostalgic desires for the food that tasted so much better in childhood. All of us have at least one dish that we have tried to emulate but have never got right, no matter how easy it supposedly is. My grandmother’s overcooked pasta with half a kilo of butter, half a kilo of crème fraîche never tastes the same when I make it. (Perhaps I am reluctant to use as much fat and don’t dare to not cook the pasta al dente). My mother’s oven-roasted potatoes remain unbeaten, as does her tarte Tatin.

Whereas it seemed most of my “pollsters” remembered savoury dishes, one friend had fond recollections of eating Scottish crumpets spread thickly with butter and jam with her grandmother: “For her, as for me, the past had a sweet taste.”

It is that “sweet taste” that is so hard to recapture, but our memories of the past are invaluable. Like food, such memories are for sharing. In response to which restaurant experience they wanted to repeat, most wanted more than anything to eat with friends again, drink a few bottles and share some tapas, mezes or “Georgian appetisers”, as well as laughter and conversation that wasn’t scrambled by zoom.

After all, though communicating via a screen is better than nothing, like faux gras, it’s just ersatz.

Let 2021 bring back the real thing! As well as a vaccine for everybody!

Here’s to the end of an unpredictable year and the beginning of a hopefully better one.

Finally, as they say in France, bonne année, bonne santé!