Guest blog by Jane Paulick: Sourdough and San Pellegrino

Life under lockdown seems to be all about food.

Food is what’s giving my days structure. Nothing fancy. But when every day is like Sunday, breakfast, lunch and dinner pin down the time, stop it floating away.

I read recipe books in bed at night, with the skylight tilted open to let in cold winter air that’s unusually crisp and fresh. There’s no drone of the planes landing at nearby Tegel airport and the faint stench of fuel they leave in their wake has gone, the air filled instead with the fragrance of blossoming cherry trees in the Schlosspark.

Pankow is eerily quiet.

Even the cats that roam the street and regularly yowl in the middle of night are silent these days.

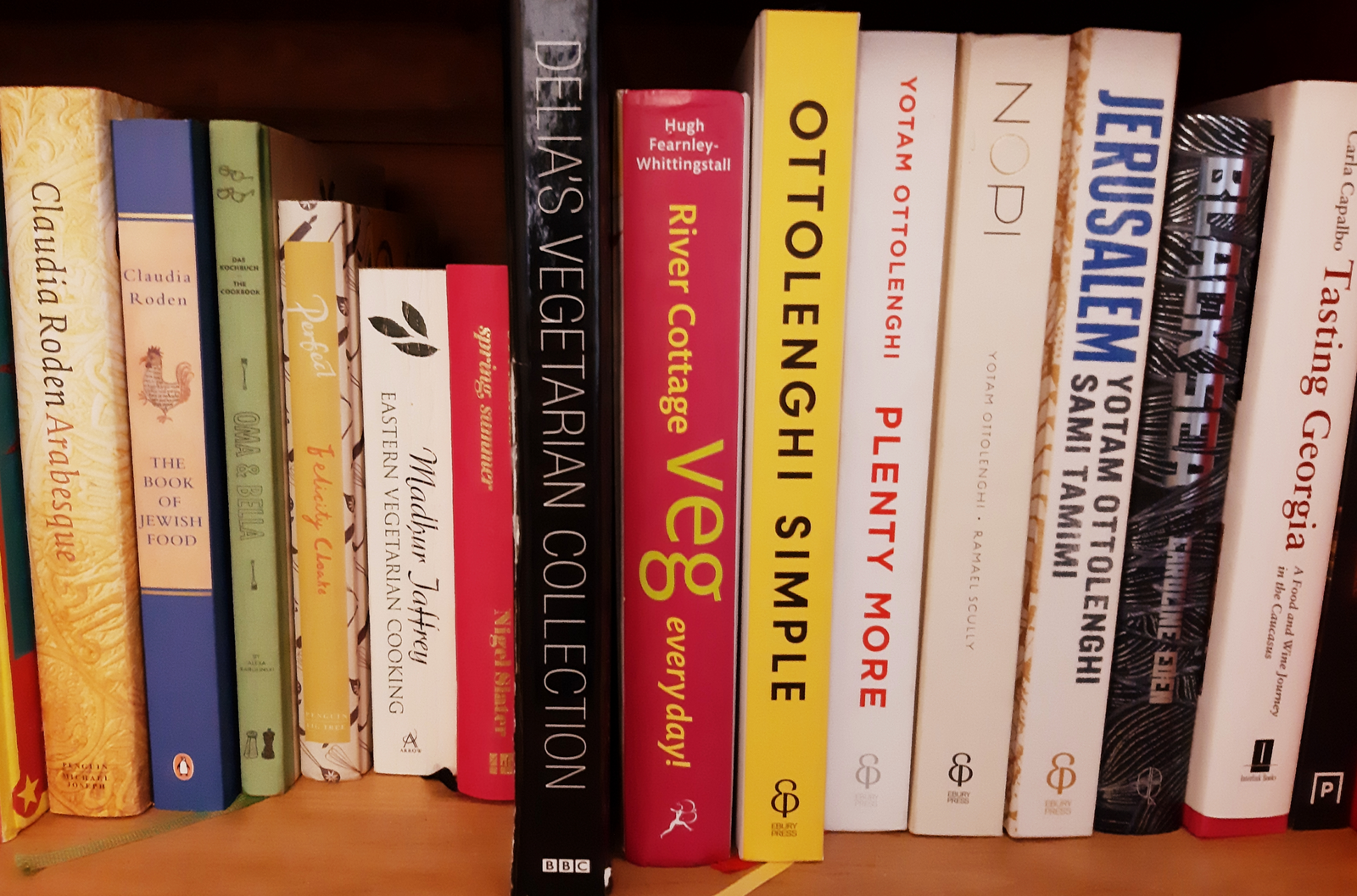

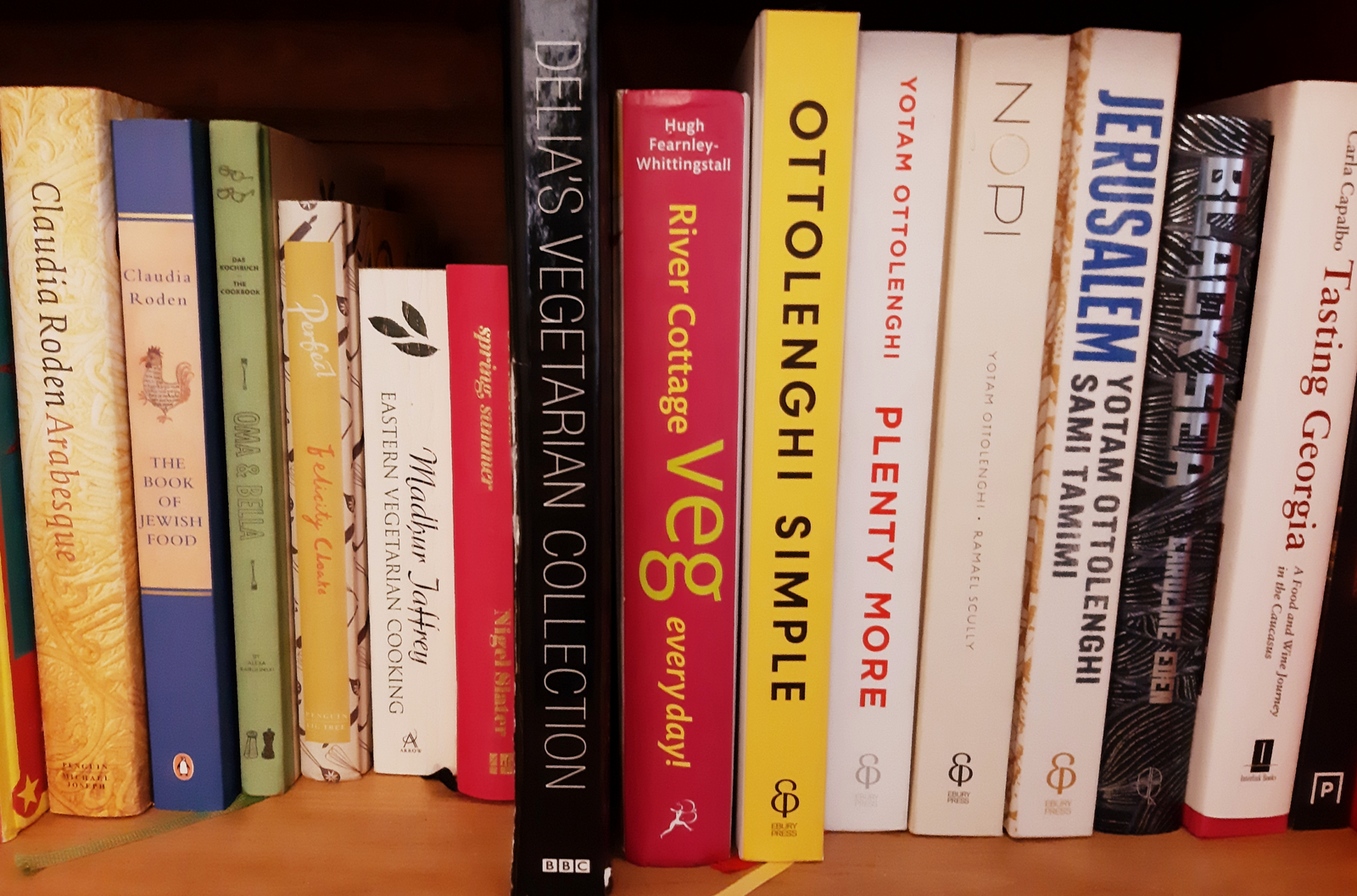

As the neighbourhood sleeps, I leaf through dog-eared editions of "The Enchanted Broccoli Forest", "Marcella’s Italian Kitchen" and "Nigel Slater’s Real Food".

For years they’ve been gathering dust at the bottom of my pile of cookbooks. But in these strange times I’m comfort eating and find myself drawn to food writers who feel like old family friends rather than cool young chefs who espouse the joys of watermelon seed butter and green banana flour. Normally I’m willing to give anything a go, but there’s a time and a place. I definitely don’t feel experimental.

The pages of the Mollie Katzen book are actually sticky, and the recipe for green chilli and cheese cornbread is illegible underneath a crust of dried sour cream.

It doesn’t matter because I know it off by heart, even if I haven’t made it for at least 15 years. In my 20s, I took that cornbread to every barbecue I was invited to.

By my 30s, I’d graduated to Ottolenghi's roasted sweet potato salad with pecans and maple syrup. I knew what sumac was. I’d moved on.

I can measure out my life with food. A friend of mine can remember exactly what she wore at every major milestone in her life. I can remember exactly what I ate.

Pink and blue iced gem biscuits on my eighth birthday, made by my grandmother (whose rule of thumb when it came to food was that if the colours match, the flavours will too).

Buckwheat pancakes the day my daughter was born. Zucchinibuletten in cheese sauce at Café Hardenberg, my first ever meal in Berlin. Stuffed tomatoes in the canteen at work on 9/11.

I’m not sure yet what food I’ll associate with the 2020 lockdown.

Enforced isolation has made me crave things that feel nourishing and soothing, and it’s made me nostalgic.

I’ve reconnected with friends I hadn't spoken to in 20 years, including one who now lives in Lombardy.

(“We’re living a nightmare,” she tells me on Skype. She’s in her kitchen as we talk, making puttanesca sauce.)

I’ve dusted off family photo albums and found yellowing pictures of my father as a five-year-old, squinting at the camera in a field surrounded by geese, a church spire behind him.

"Großhartmannsdorf, 1942", someone has written on the back in a spidery hand.

He always said he ate well as a child in war-torn Germany, growing up in the countryside of Saxony. Potatoes aplenty, of course.

In autumn there were even Kartoffelferien when children didn’t have to go to school so that they could help with the potato harvest.

He and his sister would collect redcurrants, mushrooms and wild garlic in the woods, and he remembers his mother filling wooden crates with apples and pears from the trees in their garden. They’d be kept in the cellar and would last for months. Some of the fruit would be peeled and hung in slices on the washing line to dry. There were also carrots, parsnips, beans and turnips, which were stored for winter in salt brine in earthenware pots.

Self-sufficiency has tradition in Germany. Here in Pankow, the allotment gardens in the Schlosspark are usually busy at this time of year with people spring-cleaning their wooden huts and getting the soil ready for seedlings.

Lonely and abandoned-looking in winter, in summer the gardens are hives of activity, transforming into oases of lush abundance with an embarrassment of riches. In September, there are always cardboard boxes of plums, courgettes and pumpkins on the pavements outside their fences next to handwritten signs that read "zum Verschenken" (something like "please help yourself").

Garden centers and DIY stores have been deemed ‘systemrelevant’ and Der Tagesspiegel recently declared that “Blumenerde ist das neue Klopapier" (Soil is the New Toilet Roll).

And there’s certainly been no shortage of sunshine and balmy temperatures.

But the Schrebergarten this year are weirdly empty.

Many of their owners are elderly, so perhaps they’re taking the self-isolation rules seriously and staying home. Or they’re worried about maintaining the two-metre distance rule in these higgledy-piggledy little garden communities.

It seems a shame. Surely there’s never been a better time to plant a vegetable patch so you’re ready to go off-grid if calamity strikes.

Judging by social media, people are certainly brushing up their baking skills. My Instagram feed is full of loaves. Sourdough mainly.

Apparently, it’s all about the "crumb shot" (the first time someone mentioned this, I thought I’d misheard).

Flour is the one thing that’s invariably sold-out at my local supermarkets.

It’s as though some primal instinct has been triggered by the coronavirus crisis, the same instinct that prompted the ancient Egyptians to harvest grain, grind it, mix it with water and place it over a fire.

Here we are wondering if society as we know it is on the brink of collapse, and what do we do? We all start madly baking bread, an art that goes back to the dawn of civilization. Surely that means something?

I reckon we’re subconsciously trying to remind ourselves that we have the skills to survive.

Being of an anxious disposition, I’ve often wondered how I’d cope in a global emergency.

In an article in The Guardian in mid-March (three weeks ago, in what I now think of as the ‘before-time’) I read that many countries are well prepared for threats. The populations of Tokyo and San Francisco, for example, know exactly what to do in the event of earthquake. And in Sweden, the government publishes a brochure with the title "If War or Crisis Comes". Containing advice for the public, it was first issued during the Cold War, prompted by the country’s proximity to the Soviet Union.

What would you do if your everyday life was turned around? it asks. What if mobile networks and Internet are not working? If there is no water in the taps or the toilet?

I found out the answer to that last question the other day. Around midday, construction workers on my street (still busily converting the top floor of the house opposite into a loft apartment) accidentally burst a water pipe and rang the doorbell to inform us they had to switch off the mains supply for several houses in the neighbourhood.

It's only temporary, they said.

An hour passed. Several hours passed. By twilight, I was panicking.

I’d already been outside for my hour of daily exercise, but I ventured back out to reconnoitre.

On my way to the corner shop where I planned to buy some mineral water, I found my neighbours standing patiently in line with jerry cans, waiting to fill them at a standpipe on the street set up by the workers.

I don’t even own a jerry can.

I sloped past them on my way home, armed with two bottles of San Pellegrino.

I realise I need to become more resourceful.

But I do cook. Another question on the Swedish government’s checklist is: What would you do if the shops run out of food and other goods, and it becomes difficult to prepare and store food?

This I can cope with. I must admit, I have always been a hoarder. At the best of times, I have cupboards full of tinned tomatoes, packets of chickpeas and dried apple rings.

I’m a practical cook rather than an ambitious one. I might balk at the idea of preparing a sophisticated dinner for six people, but I’m confident I could sustain my family for several months with my supply of emergency staples.

Hopefully I will never have to. But just in case, I’m going to keep studying those recipe books.