Make syrniki not war: Eat for Ukraine

Shocked by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Anne Thomas laments the horrors of war and reminisces about more peaceful times when she lived in St. Petersburg. In between demonstrations calling for the fall of Putin, she eats vareniki and syrniki in Berlin's cafes. At the end, she dances.

When I wrote my first blog post for Berlin by Food two years ago, I quoted the Italian writer Francesca Melandri: “When all of this is over, the world won’t be the same.” She was talking about the coronavirus pandemic, and she was right. Yet the pandemic pales in comparison to the war in Ukraine.

“When all of this is over, the world won’t be the same.”

What never seems to change is war.

As Putin wreaks havoc, I – like Melandri – have been attending anti-war protests in Berlin, a city visibly marked by war. The demonstrations take place in the centre, not far from the Siegessäule, a victory column erected to commemorate a variety of Prussian victories, including over France in 1871, and not far from one of the city's Soviet War Memorials that commemorate the 80,000 Soviet soldiers, many of whom were Ukrainian, who died in the Battle of Berlin. Also in the area is Der Rufer, a statue by Gerhard Marcks of a larger-than-life barefooted man calling out. Inscribed on the pedestal, are these words by the Italian poet Petrarch: “Ich gehe durch die Welt und rufe ‘Friede, Friede, Friede’” (“I go calling out: Peace, peace, peace”). And on Unter den Linden just a kilometre away is a replica of Mother with her Dead Son, a sculpture by the German artist Käthe Kollwitz, who lost her son in the First World War. As Pete Seeger asks in his song “Where have all the flowers gone?”, beautifully rendered here in German by Marlene Dietrich, “when will they ever learn?”

Days after Russia invaded Ukraine, the Maxim Gorki Theater, just behind the building in which Kollwitz’s sculpture is housed, organised an incredible event in solidarity with Ukrainians: Writers read texts by other writers. The Nobel laureate Herta Müller reciting from the works of her friend and fellow Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich, who now lives in Berlin. Just weeks before the invasion, the two had given a joint interview to Der Spiegel, which is all the more poignant today.

Selecting a passage from Boys in Zinc, about the devastating impact of the Soviet-Afghan War on the men sent to fight and society, Müller warned that 10 years from now Russian soldiers and their mothers would be saying the same.

There are already news reports of wounded Russian soldiers being treated in Belarusian hospitals. They arrive with missing eyes and ears, arms and legs, often they have gangrene, and limbs have to be amputated. At the start of the war, the Soldiers’ Mothers Committee in Russia said that young men were being sent against their will to fight in Ukraine.

As some dreamt of Putin being assassinated by Mossad or the CIA, others hoped that Russian soldiers first, and then the general population, would rise up against yet another senseless war. Neither of these scenarios seems very likely now.

Meanwhile, we have learned of massacres perpetrated against the Ukrainian population by Russian soldiers. Bucha has become synonymous with indiscriminate cruelty and suffering. There are also horrifying reports of rape.

The Russian writer Lyudmila Ulitskaya, currently in self-imposed exile in Berlin, recently spoke of the strength of women in Russia and the rest of the former Soviet Union. She expressed her conviction that it was women who would bring an end to this war. In Russian and Ukrainian Notebooks: Life and Death Under Soviet Rule and The Unwomanly Face of War, the Italian illustrator Igort and Svetlana Alexievich respectively, depict the experiences of women in the region and pay tribute to their strength.

After Russian troops marched into her town in February, a defiant Ukrainian woman scolded a heavily armed soldier and offered him sunflower seeds. She said if the troops took the seeds and put them in their pockets, sunflowers would at least sprout after they had died.

Another resourceful Ukrainian woman reportedly knocked a Russian drone out of action after throwing a jar of brined tomatoes at it.

I like the idea of a legion of women using sunflower seeds and tomatoes to confront the enemy. They could also get creative with vareniki, the vegetarian Ukrainian dumplings once given to women who had recently given birth, as well as to reapers during the wheat harvest to give them strength.

Filled with cabbage, potatoes, mushrooms, curds, or cherries and invariably served with lashings of melted butter and a generous dollop of smetana (sour cream), they surely comprise one of the most delicious comfort foods in the world.

In a delightful scene concocted by Nikolai Gogol (or Mykola Hohol to transliterate from the Ukrainian) in his short story Christmas Eve, vareniki have magic powers: They fly up and dip themselves into smetana before entering the mouth of the Cossack Puzaty Patsyuk.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the recipe could be found for my fantasy women’s army? Instead of flying themselves into the mouth of a hungry Cossack, these vareniki could perhaps be used to repel and deactivate bullets? Or even to turn bullets into vareniki that would stuff themselves into the mouths of soldiers?

For several years, in the central Ukrainian city of Cherkasy, which has been hit by heavy shelling in the past month, there even stood a monument to this national dish. Kitsch? Perhaps, but surely no less absurd than monuments erected to celebrate military victories or commemorate dead soldiers.

Returning to the realm of the possible, the best thing to do with vareniki is to eat them in large quantities. Make your own by following this online recipe or check out the recipes by Olia Hercules and Alissa Timoshkina. If you’ve not yet encountered these two extraordinary women, please read this New Yorker article about their Cook for Ukraine crusade right away.

Then, before reading any further, take a few minutes to visit their page and make a donation, and at the same time please also give to the World Food Program, which feeds hungry people all over the world. Their task has hardly been eased amid rising prices caused by the war in Ukraine. (As a friend wrote on her poster at the first anti-war demo: “Literally the last thing the world needs right now!”).

I have been following Hercules and Timoshkina avidly. My Instagram feed is flooded with information about frequent “Cook for Ukraine” events all over the world from London to Tokyo, with amateurs and professionals alike raising money. Unfortunately, the campaign does not seem to have quite taken off in Berlin, though there are many scattered fundraising efforts. Boiling Room Berlin has been organising cooking sessions. Fine Bagels took part in the Hamantaschen for Ukraine during Purim, and Bio Company has paired up with Märkisches Landbrot to sell a “peace bread,” with one euro per loaf going to Ukraine. There is also a Bake for Ukraine initiative, and two Ukrainian women regularly sell palianytsias at Markthalle Neun. Wir Wir has raised thousands of euros for Artists at Risk and Berlin to Borders selling cakes at its Bitte mit Sahne! Kuchenbasar and there is a lot of cooking going on behind the scenes for refugees arriving in Germany. For those who prefer to help by drinking, the wine bar in Weserstrasse Vin Aqua Vin is selling a very decent German assemblage for Ukraine.

Berliners, I encourage you to buy the bread and wine and to start hassling your favourite restaurants and cafes to stage “Cook for Ukraine” events. Also, what’s stopping you from organising your own? As soon as cucumber season arrives, I’ll be pickling for Ukraine, using recipes from Darra Goldstein’s Beyond the North Wind. I also recommend her recipe for syrniki, right up there with vareniki on the list of greatest comfort foods ever.

When I was in Kyiv last September, I ate these for breakfast every day. Each cafe had a different take on them, and I could not get enough.

If there are any upsides to the war in Ukraine, my hope is that some of the people forced to flee will open up restaurants here in Berlin, just as Syrians have upped the city’s culinary game since 2015.

Though not quite as good as the places I discovered in the Ukrainian capital, there is a very decent attempt at providing home-cooked classics at Drei Elephanten, a no-frills mother-daughter establishment just round the corner from me in Neukölln. Till recently it promoted itself as providing “Fresh Russian Soul Food," but now I see that it is serving “Fresh Ukrainian Soul Food”. Soul food is wrong – comfort food would be better and much less loaded, but what matters for now is the taste. The syrniki here are crisp on the outside, fluffy within, and served, as they should be, with smetana and jam – a satisfying start to the day. A little later on, you can get borsch, with or without meat and with or without smetana – a nod to the vegan locals, and of course there vareniki, with potatoes or curds, mushrooms or spinach. These are served with fried onions and mandatory smetana and are delicious. But I have to do the heavy-lifting: Not one of them deigns to dip itself into smetana and fly into my mouth! You’ll also find a whole variety of blinis, mamaliga (a polenta dish served here with mushrooms), galushki and lenivye (“lazy”) vareniki, which are not filled but akin to gnocchi, and served with cherries.

In a quiet part of Schöneberg is Odessa Mama, one of the few explicitly Ukrainian restaurants in Berlin before the war. Though far from exciting in terms of setting and atmosphere, it is the ideal place for tasting typically Odesan dishes (see Caroline Eden’s fantastic Black Sea and this website for more), such as vorschmack, baklazhaniya ikra (aubergine caviar) and Black Sea solyanka made with fish, capers and pickles. The menu also boasts deruni (potato pancakes), and of course borsch, pelmeni, blinis and the usual meat suspects. I cannot vouch for any of these dishes, but the borsch and vareniki are just as they should be.

These days, Odessa Mama has also become a collection spot for warm blankets, medicine, nappies, dried foods and tins. And tragically Odesa itself has been bombed and is preparing for more mayhem, a city which, as Caroline Eden writes, has already endured so much: “Plague, pogroms, the havoc of Communism and the agonies of Capitalism.”

She also describes the main market: “Almost every conceivable smell permeates the air at Privoz, one of the largest food bazaars in the former Soviet Union. […]” It was where I headed immediately upon arrival when I visited the city in 2018. Traders sold mountains of cucumbers, tomatoes, pomegranates, dill, coriander and spices. It was an even better version of the Kuznechny market in St Petersburg where I would stock up on vegetables, smetana, honey, dill and coriander in the 1990s.

Berlin has no equivalent. There are weekly markets where you will find fresh vegetables and of course beetroot, cabbage and dill if you’re making borsch, but for your pomegranates head to Sonnenallee or Kottbusser Damm. Order a glass of freshly-squeezed juice for a little taste of the Caucasus. No, it is not the same, but close your eyes and pretend.

If you go to the Schillerkiez market on Saturday, you can get your requisite veg, a glass of pomegranate nectar, and also a hot plate of pancakes, pelmeni or plov at Shanna’s Kochstube food truck. If you’re not hungry, you can take some frozen vareniki back home with you. Fry up an onion, melt some butter, add a dollop of cream and a sprig of dill. They are surprisingly good.

For curd cheese and smetana, you’re best off going to one of the generic stores called Rossiya, Avant-Garde or Mascha. In an essay written in the era of Trump (remember him? Putin’s friend?) and the “border wall”, the great playwright Ariel Dorfman, describes the supermarkets across the United States where he can find all the tastes of Latin America and thus his childhood and youth: “I can savor under its vast roof the presence of the continent where I was born, go back, so to speak, to my own plural origins. On one shelf, Nobleza Gaucha, the yerba maté my Argentine parents used to sip every morning in their New York exile—my mother with sugar, my father in its more bitter version.”

“To stroll up and down the grocery aisles of that store is to reconnect with the people and the lands and the tastebuds of those brothers and sisters and to partake, however vicariously, in meals being planned and prepared at that very moment in millions and millions of homes everywhere in the hemisphere.”

In a sense, the “Russian” supermarkets are similar. Located in Charlottenburg, Lichtenberg, Marzahn and around the city, they sell products from all over the former Soviet Union and even the satellite states. There will be always be an array of wine, invariably from Georgia, “shampanskoye” and vodka, dairy products from Poland, two-litre plastic bottles of kvas and the tarragon lemonade Tarkhun. There will be roasted buckwheat, oats, and semolina, often from Ukraine. Jars of pickled cucumbers, tomatoes, mushrooms, of course. Tins of sprats and herring, jars of caviar, and less expensive fish roe. Finally, to give the right finishing touch to dishes, there are spice mixes from Uzbekistan and Georgia (khmeli suneli has been translated charmingly as “spices for aliens” and apparently contains “ground mayor” whereas in actual fact it is an intoxicating mix of blue fenugreek, coriander, marigold and more). The people who shop in these stores might have Russian, Ukrainian, Armenian, or Azerbaijani origins. Depending on their age, they may have fled the Soviet Union or Putin’s Russia. They could also be so-called Russia Germans, who might have come here in the 1970s or 80s or perhaps after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Or they could be so-called “quota refugee” Jews who came in the 1990s. Or people from the LGBTQ community, who chose to live here as Russia became increasingly homophobic. What many customers share is the Russian language and certain dishes, which those who grew up in the Soviet era will have eaten more - or less - willingly.

Just as an “Asia” shop will often sell products from India, Pakistan, Korea, Japan, China and more, these “Russia” shops convey a false sense that these products are interchangeable, that people in the former Soviet Union are all “Russian” and eat the same food. This is the result of imperialism and Russification policies. The war in Ukraine is a bitter continuation of a longstanding attitude.

It is often the same in “Russian” restaurants, which serve dishes from all over the former Soviet Union even if there are no imperial intentions and only tenuous connections with the "motherland". Indeed, some of these suffered at the beginning of the invasion from the knee-jerk reaction to boycott anything Russian. The local Datscha chain of restaurants, one of my favourites in Berlin, for instance, had to make statements on social media and point out that they were against the war and that their staff members came from all over the former Soviet Union and the world, and that they were in no way co-responsible for Putin’s decision. It seems insane that people should have to do this, but just as Chinese restaurants suffered at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, "Russian" restaurants are paying the price now. These days, there are clear signs that read Make Love Not War in English and NO WAR in Russian at Datscha, Kreuzberg.

The restaurant is clearly a tongue-in-cheek post-Soviet affair. Not only can you get Siberian pelmeni and Ukrainian vareniki, but there are hipster Vladivostok or Caucasus bowls. The breakfasts reference Gorki and Pasternak, and there are jabs at the former Soviet Union across the menu, as well as in the vintage decor. Contemporary takes of classic dishes are served, and these are consistently good. As you might have figured out already, I almost always go for the syrniki at breakfast, and the assorted vareniki at other times of the day, but I’ve been assured that other items on the menu are also good.

Kvartira 62, a candle-lit bar with wooden floors, reminiscent of the cool 1990s Berlin, not minimalist hipster, is also very welcoming. Outside the bar is a billboard that says Stop the War in Ukraine and there is a Ukrainian flag inside. The restaurant has been organising solidarity poetry readings and concerts. This is the place to come for kvas, birch juice, Baltika beer (brewed in St Petersburg and a favourite of mine when I lived there) and of course an array of vodkas, from plain to flavoured, with everything from pine kernels to berries. There is also an impressive cocktail list that references cultural greats such as Alexander Pushkin and Vladimir Vysotski for instance. Here too, of course, there is borsch on the menu as well as vareniki. Depending on your constitution, order a beer and/or a vodka, and start off the evening with a tasty zakuski plate with particularly zingy pickled cabbage and a fiery carrot salad. Just the taste of the cabbage plunged me back a few decades to Money Honey, a cult rockabilly bar in St Petersburg where I spent many a wild night, only able to afford rice with sauerkraut to soak up the cheap spirits. But it is fresher, crunchier than in my memory.

While Kvartira 62 brings me back to the bars of my Petersburg days, I go to Potsdam for the architecture. Sanssouci is the closest there is to the palaces of tsarist Russia and the Alexandrovka Russian Colony boasts a dozen 19th-century wooden houses built in the izba style. The restaurant in Alexandrowka Haus 1, which also published a statement underlining that it was against the war in Ukraine, is quite delightful. Here too, the menu is almost “Soviet” with classics such as vinegret, seledka v pal’to (herring under a fur coat) and there are even Riga sprats. The soups are particularly delicious: On a blusteringly cold day in December, I wolfed down a bowl of Ukrainian borsch with gratitude. In summer, there is okroshka (a cold raw vegetable soup), and otherwise there are shchi (cabbage soup) and ukha (a clear fish soup). Then, of course, pelmeni and vareniki.

As it should be, the postprandial tea is served in a podstakannik, a tea glass holder, which I have always very much loved. I still regret not disappearing a few into my luggage on a train from Moscow to Saint Petersburg in 2012. I stupidly asked the conductor, who offered to sell me them at an exorbitant price. It only dawned on me after I’d got off the train that he would have stolen them himself. I doubt I’ll be going on a night train across Russia any time soon, so have to make do with drinking out of these holders in cafes.

For example, at the Tadzhikische Teestube. It was exhibited in the Soviet pavilion at the Leipzig trade fair in 1974 and does not seem to have changed since. The blurb explains that the origin was the Republic of Tadzhikistan where people live a “nomad life” and “teahouses are an important place of communication”. “While drinking tea, people discuss, trade, chat and enjoy the pleasure of smoking the waterpipe.” As far as I know, there is no more smoking the waterpipe, but drinking tea is still very possible and you can choose from smoked tea, caravan tea, Lomonosov tea and many more. I like to kick off my shoes, get comfortable on the cushions and drink tea with jam and a slice of flaky tort napoleon. There’s also Russischer Zupfkuchen, a classic and delicious cake in Germany, that combines chocolate cake with cheesecake, but apparently has nothing to do with Russia at all. A simple marketing ploy, which could now backfire!

I have written about the comforts of drinking tea in Britain, but it was in Russia that I discovered it was life-saving. In the cold winter months, a glass of strong tea with copious amounts of sugar and a slice of lemon would bring me back among the living when I thought that my hands and feet were going to drop off. Back then, there was no choice of tea. It was black, often Lipton. When I returned years later, I struggled with the choice.

Today, I am drinking sobacha tea. I discovered it last September in Kyiv. It was on sale at all the hipster cafes dotted around the city and I loved its nutty flavour. When I asked a cool barista if it was a Ukrainian speciality, he said “No, Japanese.” As soon as I got back, I searched for it but so far have found it only at Mamecha. Called Dattan Soba, it is described as Tartary buckwheat. I wonder if the Tatars of Crimea started the trend in Kyiv? I wonder if the barista is on the frontline today? Olia Hercules, the Ukrainian-British chef, whose praises I sang above, said recently that many Ukrainian chefs had become activists, cooking for soldiers on the front. I hope that the guys I chatted to in Kyiv are doing the same, rather than facing bullets.

I was in Ukraine for work 80 years after the Babyn Yar massacre, one of the worst mass shootings of Jews in what has become known as the Holocaust by Bullets. While there, I took part in a commemorative march towards the ravine on the outskirts of Kyiv, where over 30,000 people were shot in two days. Over five days, we installed Stolpersteine around the city to honour some of the victims and say their names. The oldest people in attendance still remembered the Second World War. The younger ones feared that their compatriots did not know enough, hoped that they would take more interest in the past. The district was one of the first targeted by Russian bombs on Kyiv this year and the memorial site was hit. There are simply no words. In this New Yorker article, Masha Gessen writes very eloquently about the Babyn Yar memorial and the current situation: “When this war is over, Europe will no longer be defined by the history of the Second World War. The next era of European history, whenever it begins, will be the aftermath of the war in Ukraine.”

Where are all the people whom I met in September today? Have they fled the country? Are the younger ones on the front? Since February 24th, I have been haunted by a film I saw last year on returning from Kyiv, when I attended the Ukrainian Film Festival in Berlin. Nous ne sommes pas encore mort (We are not dead yet) by the French director Joanne Rakotoarisoa is about a group of teenagers hanging out one night. One of the boys is quiet and despondent because he has been told to report to the draft office.

Today, boys have no more choice. Ukrainian men of “fighting age” are not allowed to leave the country. Many are now defending their country willingly – and I, a pacifist who loves the song Le Deserteur, written by the French genius Boris Vian in 1954, find myself rooting for them and donating for protective vests for soldiers, as well as for medicine for evacuees. I never thought I would become a patriot, moved to tears by a country’s national flag or anthem, but I now only need hear a few notes of this to find myself crying. My heart soars when I see yellow and blue, even if this is just a sign for Edeka or Lidl! Some say that the blue of the Ukrainian flag represents the sky over a field of sunflowers. There is apparently not much truth in this and others claim the yellow symbolizes the golden domes of churches, but my vision is of sunflowers on a sunny day.

With the war, the price of sunflower oil has risen, as has that of wheat. Even Berliners are being rationed, though less so than Russians. In an article for the French weekly Nouvel Observateur last month, the French writer Emmanuel Carrère wrote of the fears in Russia that “defizit” would soon be standard. Already, people could not buy 10 eggs as usual but nine, and maybe in future eight. Butter was no longer sold in 250g but 190g slabs and a kilo of sugar was 920 grams.

There is an old Soviet joke that could soon be pertinent all over the world: A man walks into a shop and asks, "You wouldn't happen to have any fish, would you?" The shop assistant replies, "You've got it wrong – ours is a butcher's shop. We don't have any meat. You're looking for the fish shop across the road. There they don't have any fish!"

Incidentally – talking of fish – Britain’s fish and chip shops are also reportedly forecast to suffer acutely from a lack of cooking oil and cod imported from Russia. Some 3,000 out of 10,000 are expected to close before the end of the year. Yet another unforeseen consequence of a war fuelled by oligarchs, courted for way too long by Westminster.

It would almost be comical if not so tragic. Many in Britain, one of the richest countries in the world, are already having to choose between “heat or eat” and this is only the beginning.

Meanwhile, in Ukraine, the Russian army is reportedly deliberately bombing bakeries and mills. What will people do if they can no longer make bread, pancakes and vareniki?

Last week, I met a babushka from Mariupol who told me she had been hungry for the first time in her life this year. She had heard the stories from the 1930s and 1940s. She had lived through shortages, but never had she actually been famished. I met her at Berlin Hauptbahnhof where I’ve been volunteering, helping out refugees arriving in Germany.

I had so enjoyed being in Kyiv last year that I planned to return this autumn. The idea was to take the train from Berlin via Krakow, Poland to Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Dnipro, and then on to Kyiv. We were going to install more Stolpersteine. Today, there are no trains going in that direction but we hear the names of these places constantly. Trucks bring blankets and medicine to people who have had to flee their homes. And overflowing trains arrive here with people who have no idea if they’ll ever go home again or see their loved ones. If they are lucky, they have relatives and friends waiting for them in Cologne, Amsterdam, or Paris; less fortunate ones will have been assigned a center in a small town in southern Germany; the least fortunate do not even know where they will sleep the next day.

A woman from Dnipro told me that she was never going back. A man, one of the few, said that he had only been allowed to leave because he had a disabled son; he and his family were going to try to start a new life in Stuttgart. A woman, her mother, and her 90-year-old grandmother, who had Alzheimer’s, had been assigned to Offenburg and were excited about being close to France. Their building in a Kyiv suburb had been bombed.

As they wait for their connections in the cold station, volunteers and refugees drink tea together and eat cake, sharing stories. Hearing and speaking Russian again for the first time in years, I am transported to happier times. When I lived in Yeltsin’s Russia, I was adopted by a babushka, whose family introduced me to the celebrated hospitality. Her husband had been an eminent geologist and they had travelled all over the Soviet Union and had many tales to tell. She knew about the hardships of life, but also had a wry sense of humour that had kept her going. When I would visit, there would be mounds of food on the table, but apart from her stories it was her incredibly greasy and satisfying cabbage-filled pirozhki that kept me going back – I have never tasted one since that matches my memories – and her medovik. Fortunately, Berlin boasts a number of places that do a very good version of this layered honey cake.

For example, Venue, a hipster breakfast cafe in Neukölln, with no ostensible connection to Eastern Europe at all, has two types on offer and apparently both made by the same Russian woman. One is rectangular and more spongey. The other is round as it should be and with the denser consistency that I remember. Both are delicious but go for the second for the “real” thing.

Kvartira 62 also has a very decent medovik, and there is an incredibly fresh and not too sweet one at the Georgian restaurant Kin Za, which is also collecting donations for Ukraine. Georgian food, in Tbilisi, Kyiv and Berlin, needs an entire blog post of its own, but suffice it to say here that before pouncing on the cake, you should also eat pkhali, badrijani, khachapuri and green spinach khinkali, of the like that I never saw in Georgia, but up there with some of the best I’ve ever eaten. Don’t miss out on the garlicky pickled cucumbers either. And never touch a sweet Spreewald Gurke again! If you like the food at Kin Za (and how could you not?) you won’t go wrong if you also check out Der blaue Fuchs, Genazvale, Tbilisi and Salhino. Order a bottle of strong red or an orange wine if you’re feeling adventurous, and then book your trip to Georgia.

But don’t leave Berlin quite yet, not now when spring is at its very best. The city is currently ablaze with the pink of the thousands of cherry trees given to the German capital by Japan after the fall of the Berlin Wall. A TV station launched the Sakura Campaign and the population, including school children, donated generously. It took years for the trees to arrive and the project to materialise, but what a joy it is today. In a city once razed to the ground, the trees along the former wall offer a glimmer of hope amid the post-war architecture.

Today, school children and others are raising funds for food and medicine for Ukraine, but let’s imagine that when the women of my fantasy army have defeated the enemy and this brutal war is over, they will collect money for trees instead.

Then, we will spread blankets, drink tea and eat vareniki and medovik together. But before that let's dance to this new Pink Floyd single and this rousing appeal by Michelle Gurevich: "Good bye my dictator, goodbye!"

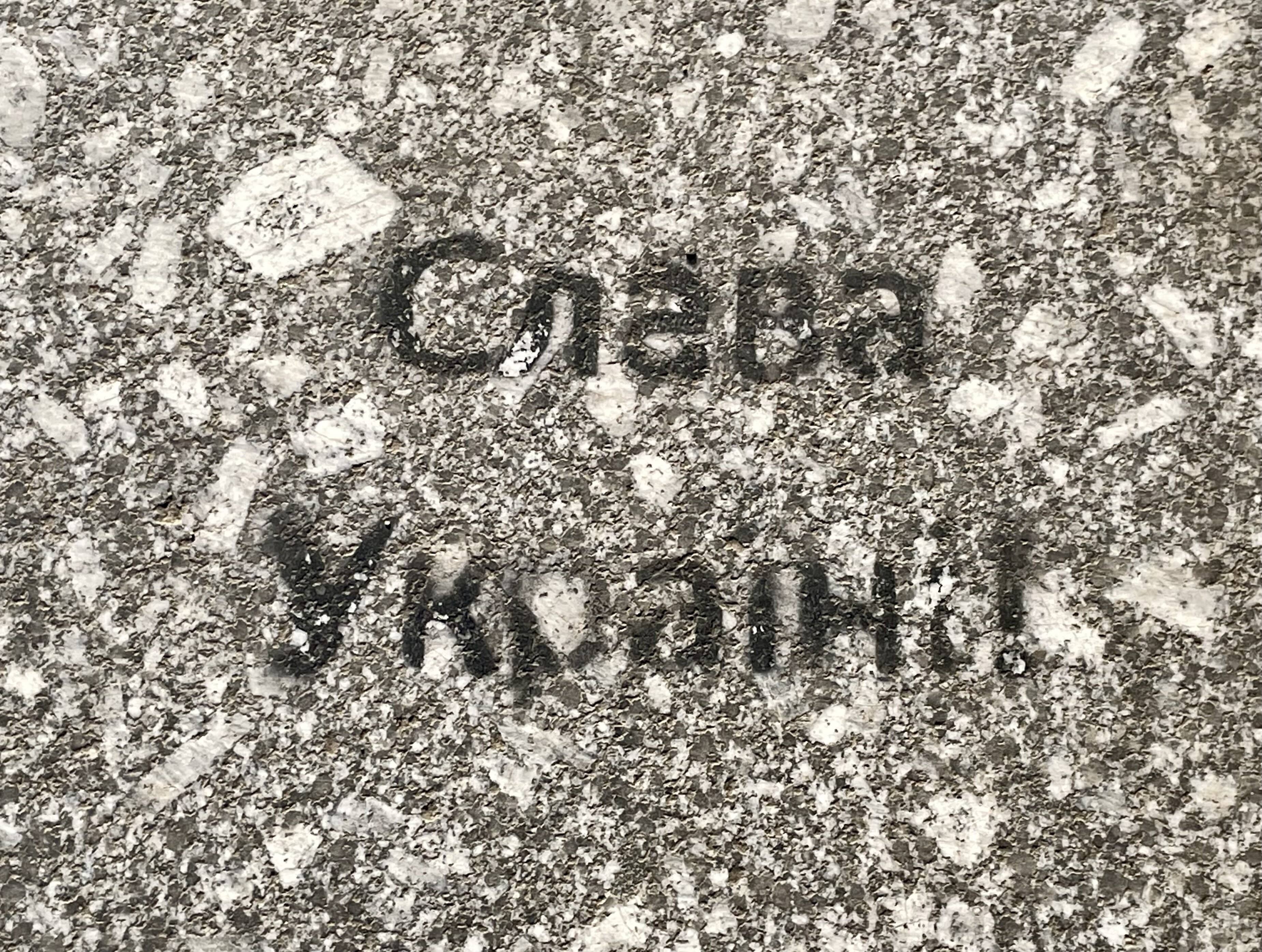

Slava Ukraini! Слава Україні!