Woman, Life, Freedom at the Berlinale

Anne Thomas set out to write about food at this year’s Berlin film festival. She had particularly high hopes about a new food court near Potsdamer Platz. But her piece turned out quite differently. Happy International Women’s Day!

This blog post originally was supposed to be about food at the Berlinale. I speculated that some of the new places that have opened up in the past year would transport me to food heaven, in the same way that the pre-and-post-film places I frequent in Bologna (see my Berlin is not Bologna post) have me in raptures. Yes, I know, that was deluded but one lives in hope (as indeed this entire post argues).

It was Manifesto that I was most looking forward to; for it had been promoted as a different kind of food court. It is indeed different from many that I have had the misfortune of eating at in the past, as the quality of the dishes is actually quite reasonable. I shared a huge plate of warm and cold mezze from Malakeh that was admittedly delicious. But it cost three times the price I usually pay in Neukölln, and took an age before it was ready.

So, in the end you queue, wait and pay a fortune to eat in a place that has bright lights and loud booming music, surrounded by squabbling families, and with a depressing view of TK Maxx and the NBA Store to boot. Hardly restorative.

Otherwise, the places are pretty much the same as before (see Allison Williams' How not to go hungry at the Berlinale post) and some of these are absolutely fine but often pretty jammed. In the end, I figured my best bet was to bring food from home or risk a rumbling stomach. Compared to what most of the protagonists in the films I was seeing faced, this was hardly tough, and the longer the Berlinale went on, the more risible my quest for decent food was seeming.

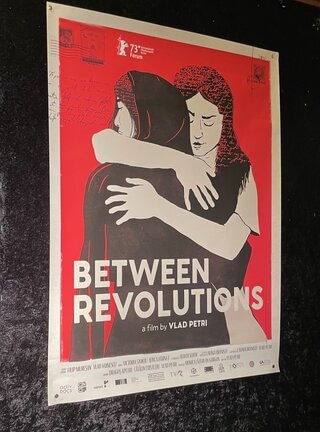

Very soon, it became clear that the focus of this Berlinale post was women. One of the most poignant moments of the festival for me was the screening of Sieben Winter in Teheran (Seven Winters in Tehran) by Steffi Niederzoll, a documentary about the young Iranian woman Reyhaneh Jabbari, who was sentenced to death and hanged after she stabbed a man who was trying to rape her.

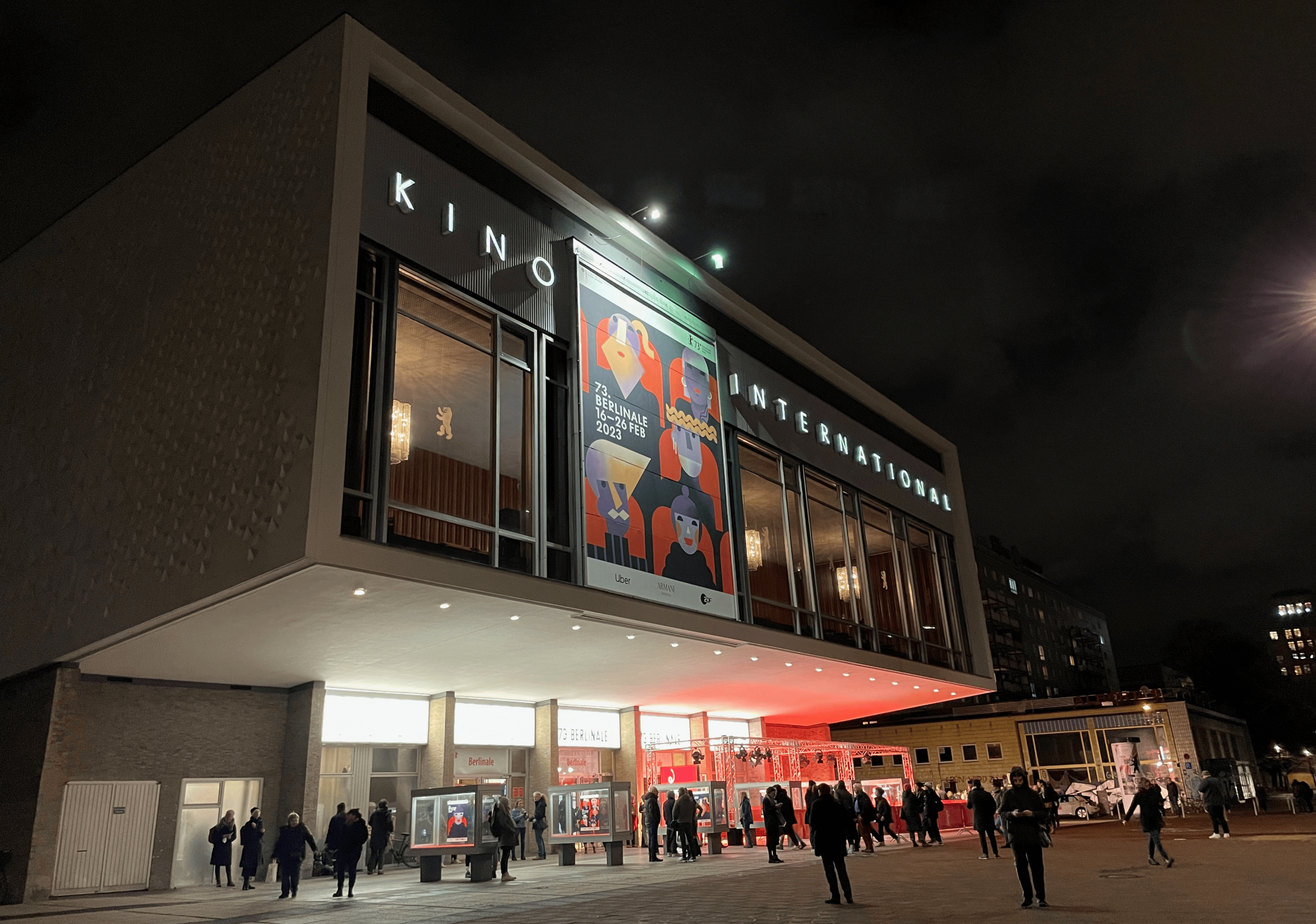

“Woman, Life, Freedom!” cried a viewer immediately as the credits rolled, and the entire audience at the imposing Kino International stood up, clapping for several minutes.

By the time the mother and sisters of Reyhaneh Jabbari came to the stage, I would wager that most of the people in the room were in tears. And particularly when Zar Amir Ebrahimi, who won the Best Actress award at Cannes last year and lent her voice to Reyhaneh Jabbari in the film, made an impassioned speech against the Iranian mullahs and rallied support for the first feminist revolution the world has ever witnessed.

This speech was echoed by the actor Goldshifteh Farahani at a session I attended of the Berlinale jury members entitled “You must be joking: Humour in serious times”, and at many manifestations of solidarity with Iranian women throughout the festival.

The feminist revolution has been a long time coming. As girls are poisoned around Iran because they dared to protest against the regime, and because there are still so many people who do not believe women should be educated, one knows that there is still a long way to go.

One day, I saw two films from very different parts of the world, and yet so similar, which both signalled that education is the way out for women. The beautifully shot and exquisitely acted Chechen film by Malika Musaeva, Kletka ishet Ptitsu (The Cage is Looking for a Bird) depicts a friendship between two girls, who like school and yet are both aware that their more likely escape from their hometown will be through marriage, and thus they hope to find someone who is at least of their choosing rather than being forced into an arranged union with “anyone” for tradition’s sake. They have limited agency but are determined to use it in their favour.

In the Rwandan film The Bride by Myriam U. Birara, as exquisitely played, a young woman named Eva who has been awarded a place at medical school thinks that she has agency until she is kidnapped and forced into marriage with somebody she has never set eyes on.

Her initial path of resistance is to refuse to talk to her new husband. She does, however, develop a strong bond with his female cousin, and this film, set against the backdrop of the Rwandan genocide, becomes one about friendship and solidarity between women. It is also one that ends on a note of optimism, as Eva decides to take her life into her own hands.

In both films, there is little resistance from older female relatives who seem resigned to accepting that unhappy marriage is the lot of women, but there are signs that younger generations will not put up with this.

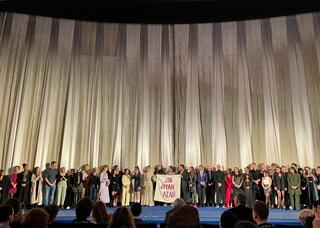

The same is true for Elaha by Milena Abayan, whose eponymous lead is played wonderfully courageously and convincingly by Bayan Layla. A young German woman of Kurdish descent, Elaha is also to be married but by contrast to the women above, she appears to approve of her betrothed. However, she is going to have to prove her virginity, and this could prove tricky. This was another powerful film that heralded a different era. It too elicited a standing ovation for the cast and team members who all came onto the Kino International stage after the screening, and unfurled a banner reading Jin, Jîyan, Azadî.

In a patriarchal society, where religious and cultural norms foster misogyny and demand that women be "honourable", rape is often part of the picture, frequently going unpunished. Reyhaneh Jabbari could have had her sentence quashed if she had withdrawn her accusations of the man she killed. She refused, as she knew that he had wanted to rape her and did not want to save his “honour”.

Some of the most agonizing scenes of the extraordinary, almost three-hour-long, documentary El Juicio (The Trial) by Ulises de la Orden, comprised entirely of footage from the 1985 trial of nine high-ranking representatives of Argentina’s military dictatorship, are of women testifying of how they were debased, tortured, and raped in detention.

One woman spoke of being forced to give birth in a car, and of not being allowed by her guards to breastfeed her newborn.

In the wonderful Sage-Femmes (Midwives) by Léa Fehner, the situation for women giving birth in contemporary France is thankfully never that dire, but some of the midwives portrayed are perilously close to burnout. Shot almost like a documentary, this warm and humourous film is about women giving birth and about those helping them to do so in increasingly difficult and dangerous conditions, due to cuts to healthcare funding. There is inspiring camaraderie between the protagonists, all of them trying to provide the best start to new lives but the pressure is palpable. One doubts that many of the midwives here will make it to the age of 62 in this profession, let alone to 64. The film ends with rousing scenes of strikes. No doubt there have also been many midwives on the streets of France this week, demonstrating against President Emmanuel Macron’s pension reforms.

After the screening, the director explained that it is mainly poorly paid, young women who are midwives in France today. Why does the state not understand that women who help others give birth to future generations are precious and must be valued? Why does the state not understand that many of the other female-dominated professions are precious and must be valued?

Over a hundred years ago, Rosa Luxemburg and Clara Zetkin were already asking these questions, and it is the latter we have to thank for International Women’s Day. Despite the progress since their time, they would be disappointed to know that equality has yet to be achieved.

Let us not wait another century for the feminist revolution to succeed! Women of the world unite!

Woman, Life, Freedom. Jin, Jîyan, Azadî. ژن، ژیان، ئازادی